KIRKUS REVIEW (an interview with Jill Ciment)

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a phosphorescent fungus threatens the health and happiness of identical twin sexagenarian sisters, their Filipino-American Shakespearean actress landlord and the enterprising Russian girl squatting in her Brooklyn townhouse closet.

No? Anyone?

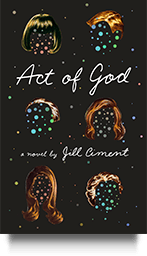

“Every writer I know wants one compliment,” says Jill Ciment, author of the aforementioned Act of God. “Some of my friends who are writers want you to say, ‘God, that was so intelligent!’ And others want you to say, ‘Oh, your language—!’ Each person has theirs, and mine is ‘original.’ That’s the big thing that I want to be, in my own privateness.”

It’s a compliment she handily earns. Ciment (Heroic Measures, 2009) writes unique novels that are provocative, funny, scenic and timely. Act of God is the vivid portrait of a particular block of Berry Street, in Williamsburg, circa summer 2015—soon to be forever changed by the discovery of a glowing mushroom in Edith Glasser’s hall closet.

What the heck is it? Where did it come from? Is it covered by insurance?

“Act of god is a legal term—the term that insurance companies use to get out of paying. After New Orleans, and even Sandy, with astronomical mold damage everywhere, there’s no reason to think that one of these things isn’t going to grow at any minute,” says Ciment, who lives in Brooklyn and Gainesville, Florida, where she teaches in the University of Florida English Department.

“That’s the moral of the story: check your basement,” she says.

As a recently retired legal librarian, Edith is quite familiar with the compensation-threatening idiom. She’s always been the steady, reliable twin, while Kat was the free spirit, traipsing across the country, falling in and out of love.

From Edith’s vantage, “Her poor delusional sister had always mistaken irresponsibility for daring, eccentricity for originality, obsession for intimacy,” Ciment writes. But, “Kat regretted nothing about her life....Only this: when they were girls, Edith had worshiped her, and now she pitied her,” she writes.

Having temporarily exhausted her options, Kat’s crashing with Edith when the ominous mushroom sprouts. For their protection, Edith swiftly contacts landlord Vida Cebu, who ignores the call. Vida recently starred in a commercial for Ziberax, the first FDA-approved female pleasure-enhancement pill, and the ignominious advertisement is distracting her from life and work.

“When I was a young, obnoxious callow student at CalArts, we used to call the actors ‘art supplies,’ ” Ciment says. “As I have aged as a writer, and my concerns are no longer just getting the skills to make a novel, which is so difficult, I’m realizing more and more that my profession is very much about acting—the idea of really embodying a character and experiencing emotionally what they would experience. And you go, ‘My god, that’s what actors do’—and I thought it’d be really interesting to write about that process.”

“When Vida stepped onto the stage it wasn’t to bask in attention, it was to disappear,” she writes. “To submit to another’s will and permit an alien soul to inhabit her body and control her expressions—all fifty-six facial muscles, and the coloration of her skin, and the tempo of her breathing, and her hair and teeth and cartilage and bones—was the deepest intimacy Vida knew. Acting gave her the only moments of respite she had from herself.”

Respite from checking her voicemail may prove to be the undoing of a whole neighborhood. But is she really to blame for the burgeoning bioluminescence? Are Edith and Kat? Is Anna Alevtina Sokolov, aka Anushka, aka Ashley, the former au pair who’s hiding in Vida’s closet, where the second outbreak was discovered?

Is god?

“This is not a novel about global climate change—but,” Ciment says. “I wouldn’t have thought of it if I wasn’t living in a world that was getting hotter, and I want literature to be relevant. I’m watching it lose its relevance. I’m watching it just disappear from the cultural conversation, except among writers, or people who work for Kirkus. And one of the ways to keep literature relevant is to try to make stories that take the temperature of the times—that’s the only way I can think of it.”

~ Megan Labrise is a freelance writer and columnist based in New York.